| Everything

has a history, including thermostat bypass systems. But before we get into

that, we need to understand why there are bypass systems. And that's easy:

from time to time, the engine will be running while the thermostat is closed.

In this circumstance, there still needs to be some coolant circulation

to address several issues: some flow is needed to prevent hot spots in

the engine, circulation is needed through the intake manifold to promote

vaporization, and finally, some circulation is needed so that hot coolant

eventually reaches the thermostat. Let's look at the historical development

of bypass systems.

In the

beginning...

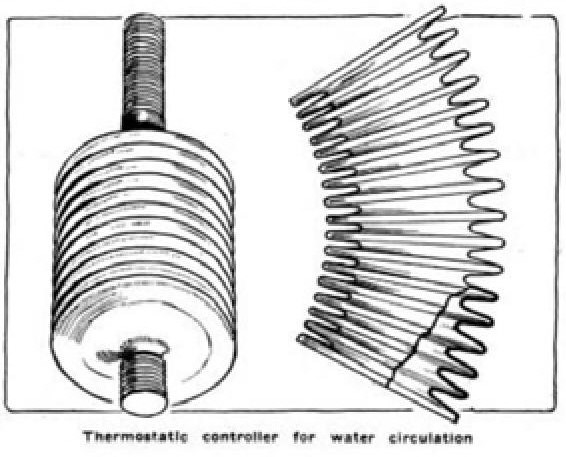

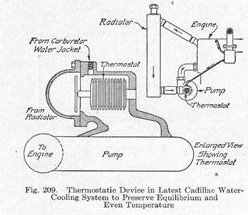

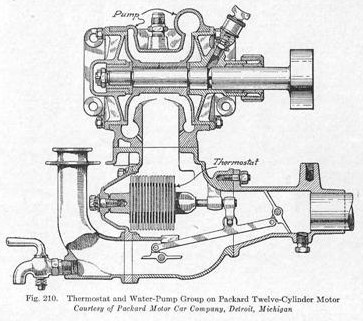

The bypass in this early Cadillac comprised a small tube leading from the carburetor water jacket to the pump inlet. This was sufficient to provide some circulation when the thermostat was closed, the clear intent being to encourage fuel vaporization. However, the open bypass was not designed to limit flow when the thermostat was open. As a result, some hot coolant always recirculated through the bypass line. The only limitation on the volume of recirculated coolant was the small diameter of the tube. Although somewhat primitive, this thermostat and bypass system allowed the Cadillac engine to develop an enduring reputation for reliability and economy which proved to be the foundation of the brand. Not to be outdone, Packard's V12, introduced in the Spring of 1915, incorporated a Sylphon bellows unit which controlled both a primary valve and a bypass:

The Packard engine, like the Jaguar V12, was essentially two six cylinder engines built on a common crank. Each bank had it's own water pump and thermostat, so the Packard was prone to some of the same problems as the Jag. The Sylphon bellows was still not built into a self contained thermostat, but operated a bellcrank system on which two butterfly valves were mounted, one controlling the bypass and one controlling the radiator passage. This allowed full volume bypass circulation, a big improvement over the Cadillac system. Thermal control was comparable to a modern engine. Gestation

By 1930, two events came together to advance cooling system design. The first was the development of the self contained thermostat. As we know it today, a brass or stainless thermostat includes the motor, valve, and support structure, and is built as a replaceable assembly. We don't even think of these things as separate parts today, but it was a new idea at the time. The other event was the acquisition of a series of thermostat companies by Reynolds Metals (as in Reynolds aluminum wrap), accompanied by a big sales push. Among the companies absorbed were Fulton Sylphon, Robertshaw, Bridgeport Brass and American Thermostat. A veritable juggernaut of thermal control. These companies would variously operate as independent or combined entities, aggressively dominating the thermostat market for many years. It's a very confusing corporate history. Buick

1931

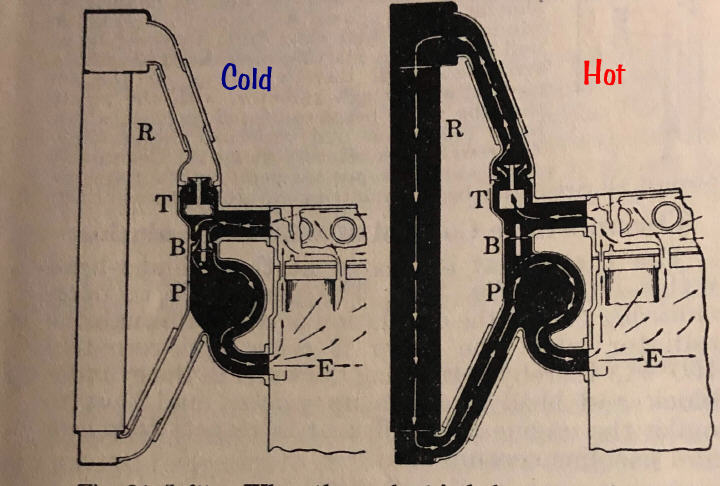

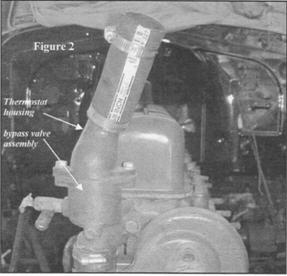

The diagram

is a little unclear, but what's going on is that a single poppet thermostat

(T) controls the water exit to the radiator (R). But a completely separate

spring loaded bypass valve (B) independently controls the bypass. The way

this works is that when the thermostat is closed, it arrests flow, which

creates a local area of high static pressure. This pressure opens the bypass

valve, allowing coolant to recirculate to the pump (P) and back to the

engine (E). When the thermostat is open, static pressure throughout the

system will be fairly uniform, so the bypass valve closes. Here are

a few photos of the bypass valve:

Eventually, this system evolved into the open bypass systems used in most American cars of the 1960's. Open bypass will be discussed in the main chapter on bypass systems. Chrysler

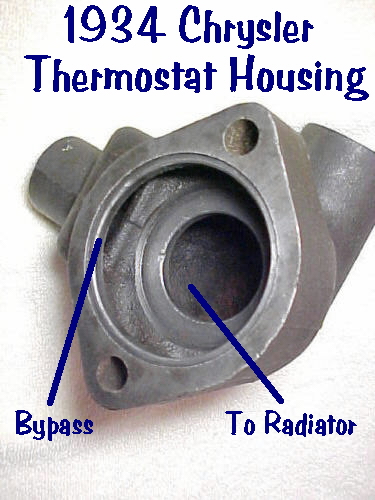

1934

Meanwhile, what was going on in Europe?

< Air Venting Main Page Bypass Systems> Copyright©2019 CoolCat Express Corp. |